What Is the Nicene Creed?

Imagine living in the generation that had to take what we call today the Old Testament writings, the Apostolic teaching that had been handed down orally through five generations, and the circulating, but not officially collected and authorized writings that would eventually make up the New Testament, and put into words a proper description of Jesus Christ. By the time of the production of the Nicene Creed, over two hundred years had gone by since the passing of the Apostles. During that time many controversies arose concerning how properly to understand and teach others about the uniqueness of Jesus’ divinity and humanity. Christian leaders had used creeds to instruct and to use as a guide for orthodoxy. However, the earliest creed, called the Apostle’s Creed proved to be insufficient for the deeper thinking about Jesus that had been taking place. The heart of the Apostle’s Creed emerged in the late second century, being used as a simple baptismal creed. It’s full and familiar form most likely was fixed during the sixth century.I believe in God the Father almighty

I believe in Jesus Christ his only son, our Lord,

conceived of the Holy Spirit, born of the Virgin Mary,

suffered under Pontius Pilate, crucified, dead and buried; he descended into hell,

rose again on the third day,

ascended into heaven,

sat down at the right hand of the Father,

thence he is to come to judge the living and the dead.

I believe in the Holy Ghost,

the holy catholic church, the communion of saints,

the remission of sins,

the resurrection of the flesh and life eternal.

Whatever early forms of this creed that were in use before Nicea, simply affirmed Jesus’s uniqueness as the Son of God and the historicity of the death, burial, resurrection, ascension, and future return. In other words, early formulas emphasized what Jesus did, but did not attempt to explain fully who Jesus was. In this vacuum of theological precision, various ideas about Jesus’ nature arose. Some Jewish Christians tended toward an explanation of Jesus that denied Jesus’ divinity. Jesus possessed a profound, special presence of God’s Spirit after his baptism and a one-of-a-kind special role, but he was not divine. These Jewish Christians could not harmonize the idea of Jesus’ divinity with monotheism.A larger threat to an orthodox understanding of Jesus was the one that accepted his divinity, but denied his humanity, popular among non-Jewish Christians. A variety of these groups denied Jesus’ humanity. The broader historical label given to these was Gnosticism. Gnostics operated from a simple, dualistic understanding of existence. All that was material was evil. All that was spirit was good. Human flesh is material; therefore, Jesus could only have had some kind of appearance of humanity, but he could not have been authentically human. One can hear in John’s first letter the gnostic heresy in the background as he emphasizes that Jesus had a genuine human existence.That which was from the beginning, which we have heard, which we have seen with our eyes, which we looked upon and have touched with our hands, concerning the word of life. 1 John 1:1 (ESV)Beloved, do not believe every spirit, but test the spirits to see whether they are from God, for many false prophets have gone out into the world. By this you know the Spirit of God: every spirit that confesses that Jesus has come in the flesh is from God. 1 John 4:1-2 (ESV)

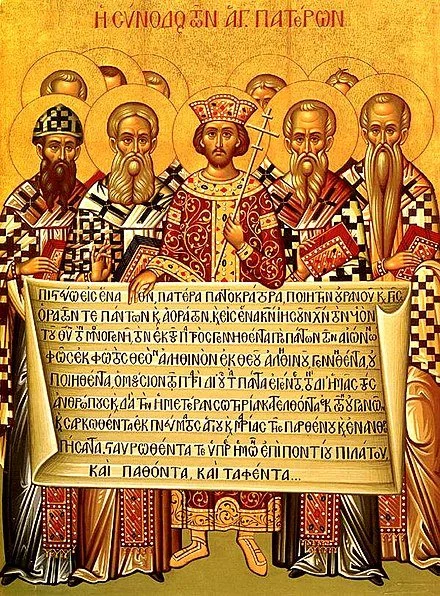

In the generations that immediately followed the apostles until Nicea, the question of authority was also a significant issue. Who was to determine the correct teachings about Jesus? Who had the authority to do so? While the apostles lived, planted churches, wrote letters and gospels, early believers knew clearly who had authority. In the next generation, disciples of the Apostles, like Polycarp, bishop of Smyrna and disciple of John, inherited the mantle of authority to pass along an orthodox faith. However, as time went on, the question of authority intensified as the lines to the Apostles grew less distinct. Bishops of the church had a certain local authority, but determining who had a wider or universal authority in the church was problematic. Therefore, two important realities preceded the council of Nicea. As time passed, and Jesus had not returned, the church needed a more precise understanding of Jesus to combat heresy and a proper authority to define and enforce orthodoxy. As if in the nick of time, the church experienced a dramatic change that would make resolving these issues possible.Debates about the nature of Jesus were nothing new before the Council of Nicea. Leaders in the church contended against extreme views of Jesus that either denied Jesus’ full divinity or humanity; however, a greater problem tended to dominate the church during its first three centuries of existence. Although theological debate went on, the existence or threat of persecution at the hands of the Roman Empire tended to warrant greater attention. Before 250, temporary and isolated persecutions would break out within the Roman Empire, like the persecution of Nero in the year 64. Although a horrible persecution, it was limited to the city of Rome. Other persecutions would come and go for 200 years. After 250, emperors enacted empire-wide campaigns to destroy the Christian movement. The Emperor Domitian enacted the worst persecution right before Christianity would become the favored religion of the empire on the eve of the Council of Nicea. The ambitious Constantine, who was one of Rome’s four rulers in the early fourth century, defeated his rivals and brought the whole empire under his sole rule. He and his last rival had officially ended persecution against Christians in 313. The previous year, Constantine had supposedly been converted to Christianity through a vision. The nature of his conversion has been greatly debated by historians. The facts are that he did end persecution, he was baptized (but not until on his deathbed), and he continued to serve as a figure head for pagan celebrations. He is a complicated historical figure. Many interpret his actions as a shrewd politician who needed a religion to be part of the glue that would culturally hold his empire together. Because Christianity had demonstrated such tenacity and resilience in the face of such horrible persecution, Constantine may have adopted the old adage, “if you can’t beat them, join them.” Regardless of whether or not Constantine was a true believer, the impact that he had on the church was profound. In 324 Constantine had finally brought the entire empire under his control and set up his new capital in Byzantium, renaming it Constantinople. Today it is the city of Istanbul. The persecution of Christians had ceased a decade earlier. But as the outside enemy disappeared, the divisions over theological views intensified among church leaders. The debate that preoccupied the church at that time centered on the views of Arius, a presbyter in Alexandria, Egypt. Churchmen debated whether Jesus should be spoken of as fully God or a created being. In the decade before Nicea the controversial teachings of Arius had found both a strong following and an equally strong opposition. Arius began his reasoning from the idea that God (the Father) held an absolute transcendent place, the only being without beginning and the source of all reality. He considered God as one, indivisible, and unchangeable. This starting point led Arius to logical assertions about Jesus, the Son of God. First, Jesus must be a created creature. He holds a first-place among all in creation and is a perfect creature, but nevertheless is not self-existent. If this is true, then it logically follows that he had a beginning. He was the first of all creation, born outside of time and the creation of the cosmos. However, he must have had a beginning. This idea created the infamous Arian slogan, “There was when He was not.” Third, Since the Son is a created being, then he cannot have any direct knowledge of his Father. The Father reveals to him what he knows. Lastly, since the Son is a created being, and not divine, he was subject to change and sin. Jesus could have sinned and fell just as Satan did. However, for Arius this was a moot point since Jesus did indeed remain sinless, and the Father knew that he would. Arius spoke of Father, Son and Spirit, but he only believed that Father was God. The Son and the Spirit, although unique in being and role, were created by God and did not share his essence. By 324, persecution from the Roman Empire had been gone for a decade and the Arian controversy had been raging for a decade. A church finally at rest had now turned from survival to debate about orthodoxy. On the throne now sat a self-proclaimed Christian emperor who wanted to create stability in his empire. Christianity was now the favored religion, and Constantine wanted both the church and his empire to be united. One of Constantine’s first major moves after gaining full control was to call for a gathering of the church’s leaders to put an end to the Arian controversy. In 325 around 300 bishops met in Nicea (in modern Turkey) for the first major church council. This was the beginning phase of the church’s institutionalization, which would lead to a variety of problems. However, it afforded leaders the opportunity to seek doctrinal unity, putting into words a faithful declaration about Jesus. In the surreal environment that now brought empire and church together in harmony, the overwhelming majority of bishops, some still bearing the scars of persecution, condemned the teachings of Arius and drafted a creed to which they required a signed commitment. The creed effectively set parameters for theological language about Jesus, the Son, while not trying to solve the mystery of the Trinity.We believe in one God, the Father almighty, maker of all things, visible and invisible; And in one Lord Jesus Christ, the Son of God, begotten from the Father, only-begotten, that is, from the substance of the Father, God from God, light from light, true God from true God, begotten not made, of one substance with the Father, through Whom all things came into being, things in heaven and things on earth, Who because of us men and because of our salvation came down and became incarnate, becoming man, suffered and rose again on the third day, ascended to the heavens, and will come to judge the living and the dead; And in the Holy Spirit. But as for those who say, There was when He was not, and, before being born He was not, and that He came into existence out of nothing, or who assert that the Son of God is from a different hypostasis or substance, or is created, or is subject to alteration or change – these the catholic church anathematizes.

The creed’s focus is clearly on the nature of Jesus. The key theological word employed in the creed is homoousios, meaning “one (same) substance.” Jesus was not a created being, but just as much God as the Father. Later statements and further revisions of the creed would continue to crystalize language about Christ in reaction to further Christological debates over the next 125 years. When the Council of Nicea concluded, Arianism had been condemned and Arian churchmen had been banished from their positions. However, Arianism would continue to be a contentious topic within the church for another generation. However, the Nicene Creed served as a watershed moment for Christianity. It was the first creed fashioned and approved by the consensus of church leaders. It became a theological standard for correct belief (orthodoxy), with particular emphasis on Jesus. This standard was erected for the church 72 years before the official canonization of the New Testament at the Council of Carthage in 397. Although these early councils and creeds properly belong to the early years of the Roman Catholic Church, Protestants can still appreciate the problems that needed to be solved, the difficult context in which early Christianity operated, and the quality of the creeds that emerged. These creeds providentially served to guide the church, preserving a biblical view of the Trinity and the gospel in a world in which the vast majority of Christians had little to no access to the Scriptures. The Nicene Creed became the early foundation for an orthodox Christology on which further creeds were built. Nearly seventeen centuries later it’s faithfulness to the Scriptures now easily accessible in a much more literate world is clearly observable, affirming God’s providential superintending.